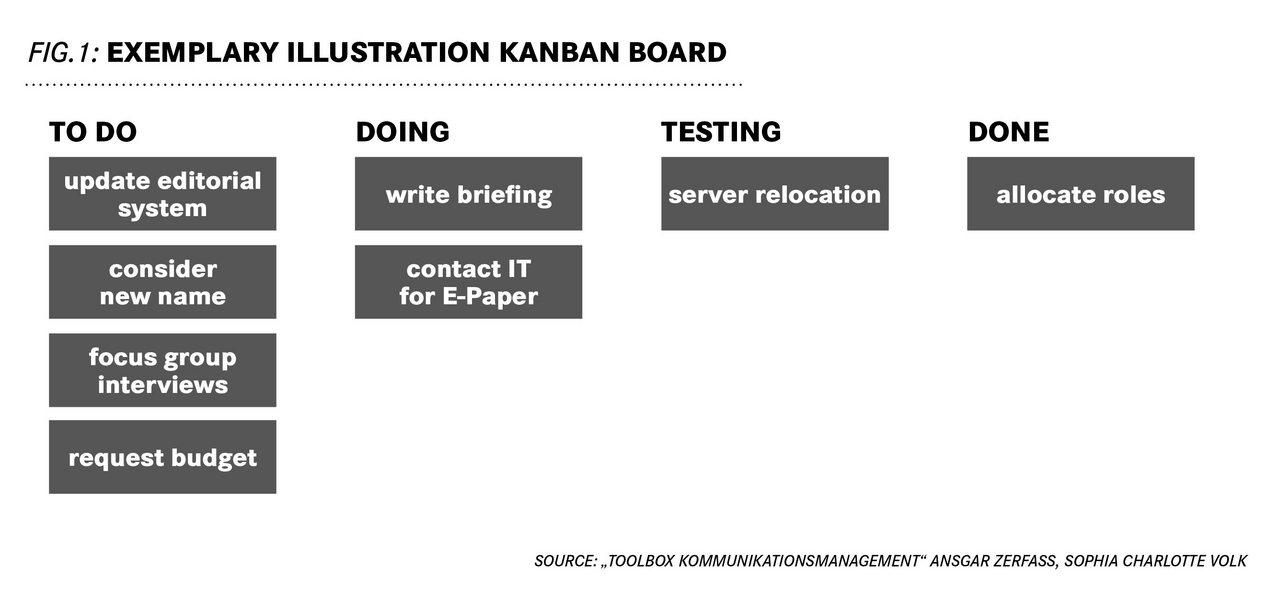

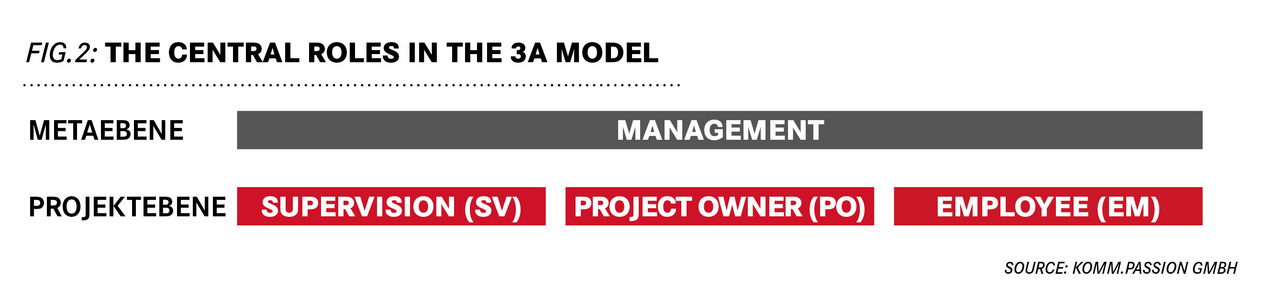

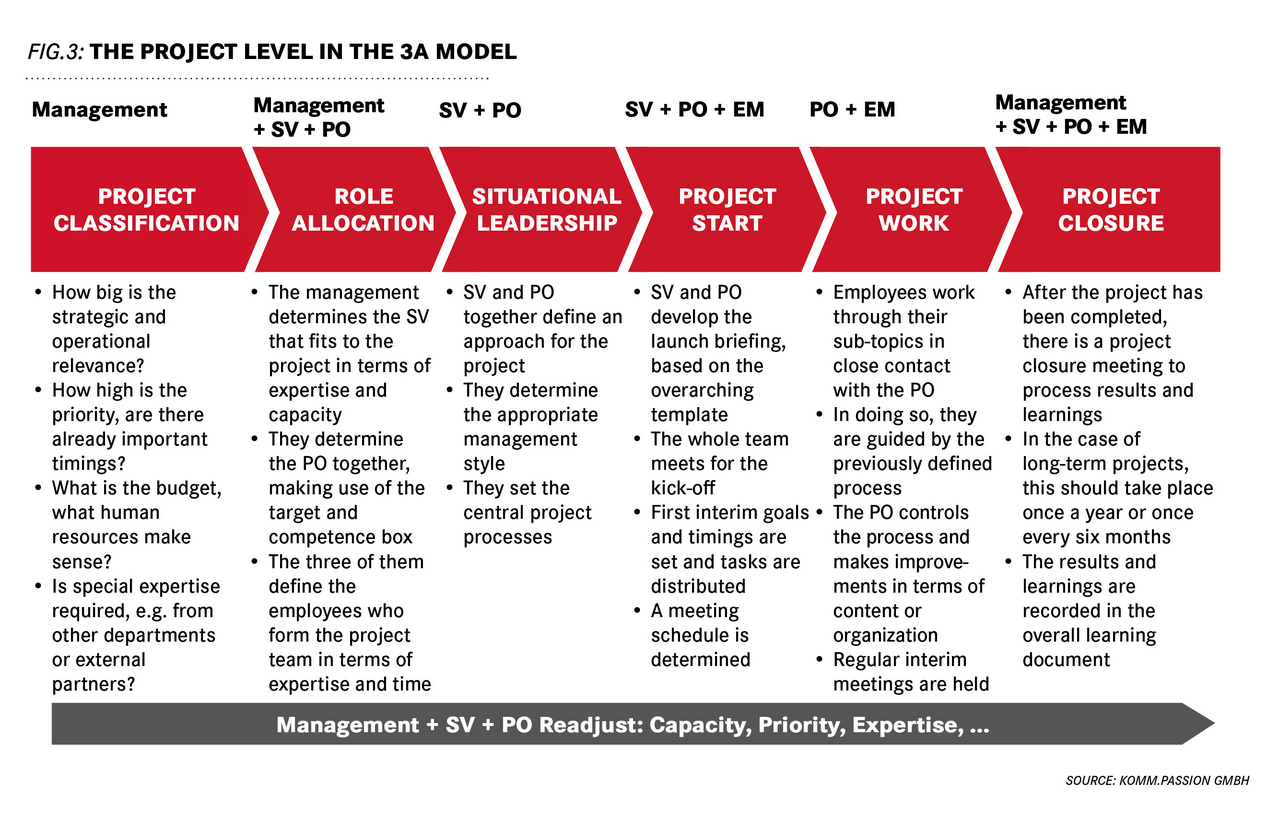

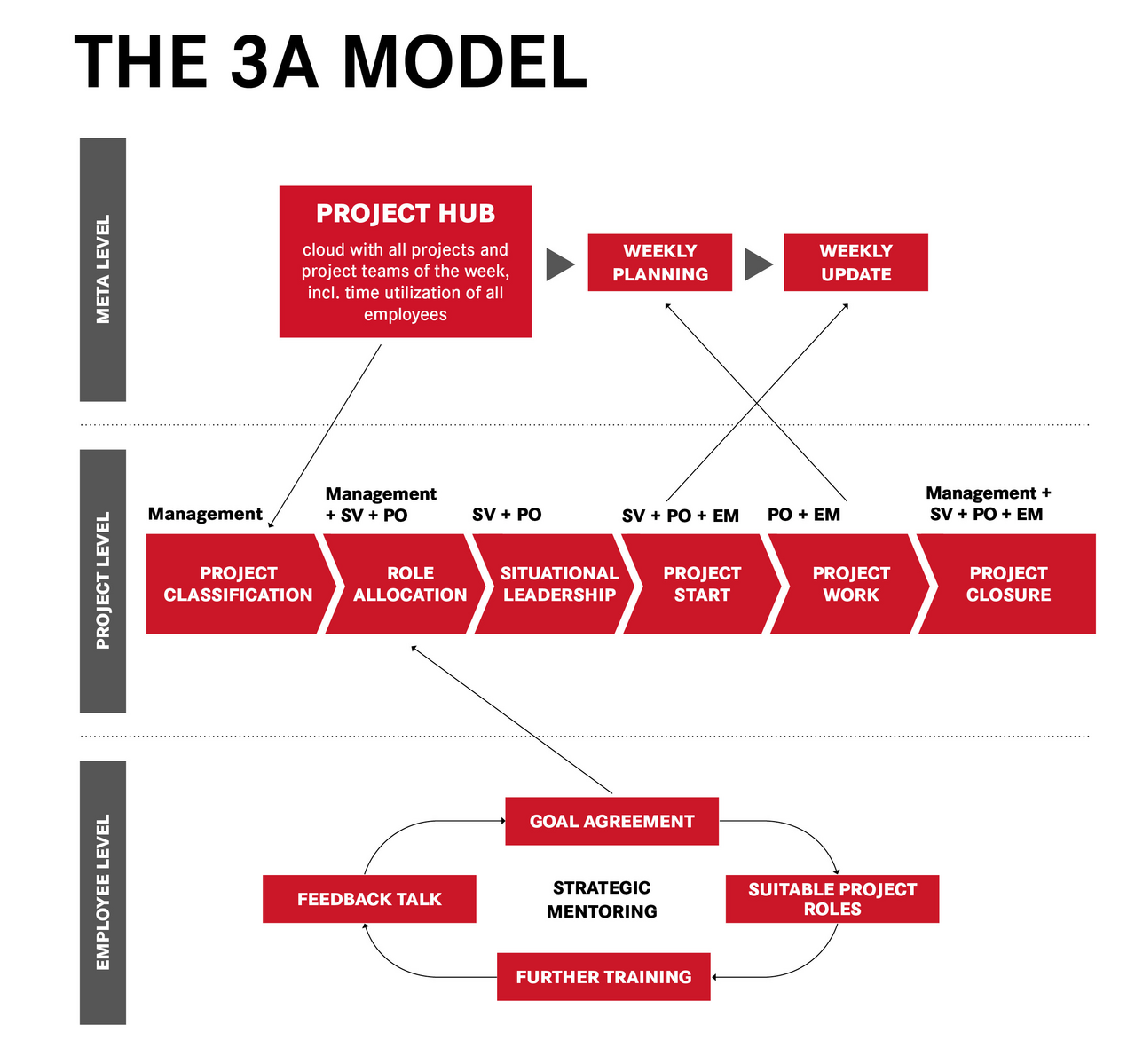

Agility is very much in style. However, the most common work models only fit the process world of corporate communication to a limited extent. Kanban, for example, comes from the automotive industry, Scrum from software development and Design Thinking from research on creative problem solving. Of course, these approaches have many elements that can be usefully transferred to communication. But is that enough? Or is it time for a specific model to make processes and organisation in communication departments and agencies more agile, more efficient, and better? This is the idea behind our model: the 3A model – Agile, Adaptive, Accountable.

| Name | Provider | Purpose | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| be_typo_user | komm-passion.de | Backend login | Session duration |

| PHPSESSID | komm-passion.de | User recognition | Session duration |

| cookieoption | komm-passion.de | Opt-in cookie stores the visitor’s cookie settings. | 30 days |

| watchedVideo_* | komm-passion.de | Store if the visitor has previously visited the website. If installed, the intro video is not displayed. | 30 days |

acceptIframe_* | komm-passion.de | Stores whether the user has allowed an iframe to be opened. | Session duration |

komm-passion.de

komm-passion.de